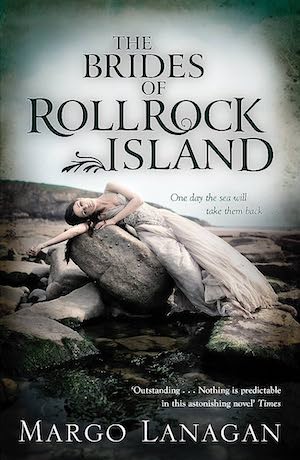

Margo Lanagan is not an easy author. Her books are beautifully written, densely constructed, and often rather dark. Her selkie novel, titled Sea Hearts outside of the US, takes the legend and the folklore and does very interesting things with it.

It takes a little while to figure out how to get into the story. Seven viewpoints weave in and out, and the first one is one of the last chronologically. But the writing pulled me in, and after all I was there for the selkies.

The heart of the story is Rollrock Island, in a vaguely Irish/Scottish/secondary-world-Celtic part of the world, more or less in the twentieth century. Buses and cars on the mainland, but no computers or cell phones.

The people there have close and ancient ties to the seals, with legends of selkie ancestors–or mermaids, as the novel calls them. When the chronology of the story begins, they are all redheaded, with an occasional dark-haired throwback. That changes, and the agent of the change is the protagonist: the witch Misskaella.

I use the term protagonist in its most precise meaning. She’s the one who drives the plot. The other viewpoints have important roles to play, but it’s all Misskaella’s fault, one way and another.

In this world, a child can wake up to magic as she grows toward puberty. Magic transforms her perception of the world; it gives her great power, but it also makes her vulnerable. Folk tradition gives her a means of suppressing this perception so that she can function among normal humans.

Misskaella is a misfit in her large family. She’s not loved or liked. Nor does she have any beauty to trade in the marriage market. She’s built like a seal: short, round, with tiny feet.

What she has as she matures is the power to peel the skins from living seals and extract the sparks of humanity inside them. The first of those, the king of the seals, becomes her lover, and she conceives a child, which she manages to conceal from every other human. But the child, it turns out, can’t thrive on land. To her great grief, she has to give him up to the sea.

By this time Misskaella is well past what most humans would consider sanity, and she has a rankling grievance against the people of the island. She concocts a plan. She will become rich, and she will become powerful. And she will make sure that everyone else is at least as miserable as she is.

Enter the brides of the US title: seal women extracted from their skins by Misskaella’s magic. They are irresistible to the men, and they are unable to resist the magic that binds them to the land. Misskaella charges high prices for the brides, and the men bankrupt themselves to pay those prices.

The seal women are all slender, dark, and beautiful, and completely submissive to the men. The human women, the red women as they’re called, cannot compete. One by one and then en masse, they take their redheaded children and depart for the mainland. In the end, there’s none left.

By this time all the couples are redheaded men and dark submissive women, and all the children are male. It’s not completely clear, but it seems that if daughters are born at all, they’re like Misskaella’s own son: they can’t survive on land. They’re given to the sea.

But Misskaella’s plan is not quite complete. She sends one of the men to the mainland to find her successor, another young woman who has grown into magic. He takes his son with him, and the son meets the first girl child he’s ever seen. She’s brash, outspoken, and completely alien to his experience. And that’s an echo of the past, and a harbinger of what’s to come.

The legend of the half-selkie children fulfills itself in the novel, when some of the sons conspire to rescue their mothers’ sealskins and help them go back to the sea. We learn then that the seal-women have ample magic of their own. They don’t need Misskaella to fashion skins for their sons, or to wrap them in the skins and transform them into seals, and take them all into the sea.

No women or children are left on the island, only men bereft of both wives and sons. Some of the men beg Misskaella and her apprentice, Trudle, to call new wives, but the witches refuse. They aren’t looking to become richer, and they’re not there to make anyone happy. Quite the opposite. It’s all about the misery.

Over time, and at first accidentally, seal hunters find the sons, and extract them from their skins—mostly alive. It’s a hard transition for them, back to human form and life on land, but for the most part they manage. And then the first red woman comes back, stubborn enough to resist the pressure to stay away, and desperate enough to claim the house she inherited from her father.

She also claims the boy she met on the mainland when they were both much younger. It’s the same boy, Daniel, who helped the seal-wives return to the sea, and who lived in the sea until he was captured and brought back to his human form. Between them they restore the balance on the island, men married to women who are their equals. But Daniel never forgets that he lived once as a seal.

As for Misskaella, she dies in a kind of dark contentment, having done everything she set out to do. Trudle has a solid handful of redheaded daughters by then, with no fathers to vex her, and Misskaella’s house and her hoard of possessions to keep her in comfort. At the last, she discovers Misskaella’s deepest secret, the one no one ever knew: three tiny nightgowns hidden deep in her house, all that’s left of three sons whom she gave to the sea.

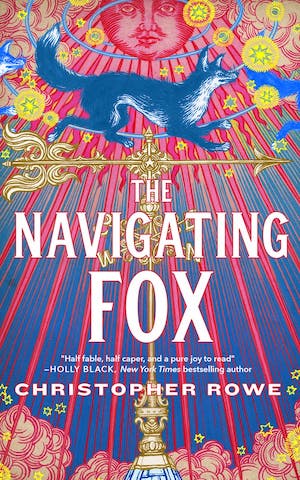

Buy the Book

The Navigating Fox

The implications there, the hints of story we get from it, are most intriguing. The witch sought magical love three times, and paid the price for it each time; she knew what would come of it, but she kept coming back. She was just as much the victim of her own sexual desires as the men.

Or did she really love the seal king? And what did he think of her? She never bound him to the land. She called him to her, but then, three times, she let him go. In that much at least, she was a better person than the men of Rollrock.

Fairy tales and folklore delve deep into the human psyche, and arise from deep inside it. Lanagan’s novel takes the legend of the selkie, of the human man who steals the seal-woman’s magic and binds her to him, and turns it inside out. She plays with the role of the witch, too: the original fairytale villain, the ugly old crone who casts her ill magic over hapless humans. Misskaella’s magic may come at least in part from her selkie ancestry, or it may come from the earth itself, or her human heritage. Whatever its origins, it twists inside her, as she grows up unloved and undervalued, used and abused by her family. She teaches the men of Rollrock Island a brutal lesson: Be Careful What You Wish For.

Once she’s set her plan in motion, she’s content to let it go as it wants to go. She doesn’t try to stop the boys from finding their mothers’ skins, or the mothers from escaping to freedom. Nor does she do anything to stop the sons from being restored to their fathers. She’s made her point. That’s all that matters to her.

The novel sheds a harsh and all too clear light on traditional gender roles. The witch gives the men what they think they want, and shows them what happens when they get it. She doesn’t care what that does to the women of either species.

Lanagan’s seals are very much not human. Even when forced into human form, they’re strange, alien, and almost incomprehensible to the men who hold them captive. Their sons have a wider view of the world, and a greater understanding of both halves of their heritage. In their way, they become what Misskaella is: misfits, caught between two worlds.

As dark as the novel is, it ends on a surprisingly hopeful note. Life goes on. People find ways to make things work. Even a wicked witch can get some satisfaction out of it, and maybe a little joy, too, one way and another.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.